Daniel Kahneman: Thinking Fast vs. Thinking Slow

Vocabulary

1. Complete the row

2. Answer the questions

- What is the difference between system one and system two thinking, as explained by Daniel Kahneman?

- Why is it important for business decision-makers to understand the difference between system one and system two thinking?

- What characterizes system one thinking? How much control do we have over it?

- How is system two thinking distinguished? What can we do deliberately within system two?

- What kind of mental work does system one handle automatically?

- Why do decision-makers sometimes mistake being in system two for being in system one?

- Does system one thinking often lead to mental errors or bad decisions? What factors influence this?

- Can you provide an example of a cognitive illusion discussed by Daniel Kahneman?

- What is “cognitive ease” and when does it occur?

- What kinds of mistakes are people prone to when they are in a state of cognitive ease, with system one thinking dominating their decision-making?

- Is it generally good to follow our first impressions and intuitions, according to Kahneman?

- Is the gut always right 90% of the time, as some may believe?

3. Fill in the gaps

4. Complete the Summary

Transcript

We’re lucky today to have the Nobel prize-winning psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman, whose book Thinking Fast and Slow is one of the bestsellers of last year and a great manual for how to make better decisions. Professor Kahneman is also a partner in the consulting firm the Greater Good. Professor Kahneman, thank you for being here.

It’s a pleasure.

Your book makes use of a very useful analogy. In fact, the analogy is built into the title Thinking Fast and Slow. System one is thinking fast; system two is thinking slow. What’s the difference between the two systems and why is it important for business decision-makers to understand the difference?

Well, system one is essentially what comes up automatically in your memory. So when I say 2+2, something comes into your head. When I say your mother, an emotion comes. So all the things that are automatic, that’s what I call system one, and you have no control of it because it’s automatic and involuntary. System two, the slower thinking, is distinguished really not so much by the fact that it’s slow, though it is pretty slow, but by the fact that it’s effortful and deliberate. So what you can do deliberately, you do in system two, and you can control yourself, control your thoughts, perform complicated computations. Those activities are system two. So system one does most of the mental work automatically. We don’t have to worry about where to put our next foot or what word should come next. Some of the work, and it’s important work, is done by system two when we slow down.

Do decision-makers sometimes think they’re in system two when they’re actually in system one?

I think mostly. I think most of us feel that we have reasons for what we’re doing, but in fact, we do what we’re doing very largely because of reasons that we’re not necessarily completely aware of. And then when we’re asked why do you do this, we have reasons, but the reasons are not necessarily the causes of our action.

Does it lead to mental errors and bad decisions because you think you’ve made a deliberation and you haven’t?

It really depends on whether you’re very skilled and whether the world provides support for your skills. So, if you’re a chess player and you make very quick decisions about your next move, if you’re a master chess player, they’re going to be good moves. But the world is not like the chessboard, so it’s more complicated. And in the world, a relatively good move is not necessarily successful. So it’s much more complicated, the relationship between moves and outcomes. Sometimes system two, slowing yourself down, has advantages and enables you to see things that system one doesn’t.

You’ve often talked about, and one of the things that has given your research such purchase is that people often make mistakes because they’re in system one. And even if they know that they’re in system one, even if they’re aware of the mental shortcut or a short circuit, if you will, that they’re doing, they can’t help themselves.

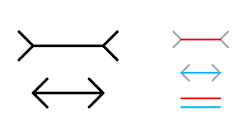

Well, you know, this isn’t familiar to everybody from visual illusions. So, there are those famous illusions where we have two lines and one looks longer than the other, and I tell you that they’re of equal length, and one continues to look longer than the other. The problem is with what we call cognitive illusions—the illusions in thinking—that it’s never quite as clear-cut. You know, you really believe that you’re wrong with a visual illusion, you really believe that you’re wrong. But with cognitive illusions, it continues to feel right. So you have an error; somebody tells you it’s an error; your better self tells you it’s an error, but it still feels right.

Can you give an example?

Well, there are people, psychopaths, who instill a lot of confidence. You know you shouldn’t believe them because you’ve been warned against them, but you feel warmth toward them, and you feel that what you have been told must be a mistake because you know that person is so charming. That’s a cognitive illusion.

Yes, some people trusted Bernie Madoff and insisted that he was good, although they were warned.

That’s the key. There was something very compelling in him, and the feeling that he elicited was stronger than the warnings.

System one, the intuitive, fast-thinking system in which most people spend most of their time, operates in a state that you call cognitive ease, while system two requires something you call cognitive strain. When you’re taking the easy path of system one, what kinds of mistakes are you prone to?

In the first place, you are going to act more impulsively. You’re going to act quickly, so if your impulses turn out to be wrong, you know, if you’re not a chess player but you’re sort of living in a world where first impulses are not necessarily wrong, you may make mistakes. By the way, not all mistakes are avoidable, but there are some mistakes that if you brought system two to bear, if you slowed yourself down, you could avoid. So, when you are in a sort of free-flow mode of cognitive ease and system one is running the show, you’re going to be more impulsive, more emotional, more optimistic, and you’re generally going to follow your first impressions and your first intuitions.

Isn’t that good? Haven’t we read that your gut is right 90% of the time?

No, it’s not right 90% of the time. The chess player’s gut, if the chess player is a master, is right 90% of the time. Those are situations that allow for skill, but when we’re dealing with situations like whether to invest in this or that, we’re not always there. The first impulse is not necessarily right the first time.